〰

The Independence of the Baltic states was decided here.

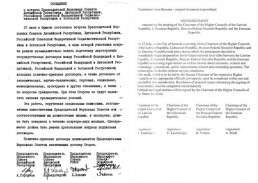

The history of the Benjamin house is a microcosm of the history of Europe in the 20th Century. The house at Juras 13 was declared a State Monument by Premier Nikita Krushchev already in the 1950s and used as a Presidential Residence and Soviet Government Guest House. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, it became the headquarters of The Baltic Council. Here, in the name of Russia, President Boris Yeltsin decided on the recognition of the independence of the Baltic States which was signed on the 24th of August 1991 at the Kremlin (see included television reportage) and later on the smooth withdrawal of the OMON (a special Milicija (Soviet Police) Unit that had been at the forefront of the violence in January and August 1991). Here in 1992 at the request of US President George Bush (the elder) the Prime Minister of Sweden Carl Bildt worked out a joint resolution with the leaders of the Baltic States for presentation at the 9 June Helsinki Summit, to Boris Yeltsin concerning the withdrawal of all Russian troops from the Baltic Republics by 1994, to which Yeltsin agreed.

〰

President Boris Yeltsin's crucial visit to the house at Juras 13, in late summer 1991, when in the name of Russia, he decided to recognize the independence of the Baltic States.

Baltic Council Summit on the 27th of July 1991: Yeltsin with the three Baltic Chairmen of the Higher Councils (Gorbunov, Ruutel and Landsbergis) in the Music room of Juras 13.

Yeltsin walks in the garden of the house at Juras 13, 27 July, 1991. Note also Alexander Korzhakov (second from the left – in the back) who became the Commander of the new Russian Presidential Security Service.

The Baltic Council was initially the informal organization of the independence minded leaders of the three Soviet Republics as they coordinated their actions and rallied support in the West for the restoration of the pre-war Republics of Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia. After that goal was achieved, the group lived on, now formally recognized as the voice of the combined Baltic peoples. The house at Juras Str. 13 was their main meeting place both before and after the restoration of independence.

Baltic Council meeting on the 6 of June 1990 at Juras 13 chaired by A. Gorbunovs.

〰

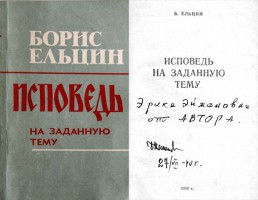

At the end of July 1991 Boris Yeltsin, attended a session of the Baltic council and met the three Chairmen of the Higher Councils of the three Baltic countries, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Boris Yeltsin still had fond memories of the Benjamin House from his stay there with his wife back in the summer of 1987 and again in 1990, which, the house staff recalls, he enjoyed very much.

While at the house, A. Gorbunovs organized a party for Boris Yeltsin to help finally relax. But Gorbunovs was not alone; he had invited the leaders of the other two Baltic Countries, Landsbergis and Ruutel to come as well. The head of Mr. Gorbunovs office, Ms. Karina Petersone recalled that the atmosphere was not diplomatic but rather cozy and the vodka flowed freely. Of course, the issue of the declarations of independence were on everyone’s mind, but not said. They all agreed to meet again the next day and Yeltsin had to be helped up the stairs to the ornate master bedroom. The next day the Baltic leaders waited until early afternoon for Yeltsin to come down. Their meeting started six hours late, but Yeltsin had done his thinking while upstairs and when he did come down, he announced to all present that Russia would recognize the independence of the three Baltic Countries without reservation.

Ever since the death of Stalin, the Soviet Union had proceeded to go through a cycle of attempts at “reform”, followed by attempts to maintain the status quo, followed by another cycle and another… until its demise. But, the Communist system had an inherent block to any real reform. Perhaps the most concise explanation of that block is written in Mao Zedong’s “Little Red Book”, in which he states: “communism is the most complete, progressive, revolutionary and rational system in human history” (page 23 of the 1st English Edition). How could anyone even consider that something like that would need reform? However, by the mid-1980s the creeping but steady decline of Soviet economic power relative to other major powers had reached such an obvious level that it could no longer be ignored. Mikhail Gorbachev’s rein as the General Secretary (Chairman) of the Soviet Communist Party and Premier of the Soviet Union was the final attempt at “reform”, “Soviet style”.

There is no question that Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev did try to really change the Soviet system, but it is equally fair to say after six years of his rule, that he was not succeeding. The vast majority of the nomenklatura, (Soviet bureaucracy) while paying lip-service to the statements of their Chairman were above all determined to protect their warm chairs and that meant preventing change or at least making sure that any changes that did happen, took place at a snail’s pace. To minimize resistance to his moves, Gorbachev adopted a “two steps forward, one step backward” policy much like an icebreaker pushes through ice too thick to just shove aside. Boris Nikolaevich Yeltsin’s career and relations with Gorbachev were a classic example of this policy.

Gorbachev became acquainted with Yeltsin while the latter was the first secretary of the CPSU Committee (Communist Party boss) of the Sverdlovsk Region, a relatively minor position. But Gorbachev recognized Yeltsin’s reformist ideas and when Gorbachev became the General Secretary of the Soviet Communist Party he maneuvered Yeltsin into the position of First Secretary of the Moscow City Committee of the CPSU (the “Mayor” of Moscow). At first they worked well together and Yeltsin was also allowed a taste of the privileges of high Party position, at one point for example getting to vacation with his wife at the Soviet Government guest house in the City of Jurmala, known as the “Benjamin House”, where Gorbachev and his wife had vacationed earlier. Later, Boris Yeltsin was to use the house as a haven during the struggle in the Kremlin. But at this time Yeltsin had become impatient with the slow pace of reform, spoke out about it and got sacked by Gorbachev; for the moment anyway.

However Gorbachev was making some progress with reforms, particularly in the legal field where, since laws, of necessity must be public, behind the scenes foot dragging was not as effective. Most significantly, Gorbachev successfully legislated the end of the monopoly of the Soviet Communist Party as the only legal political party. This, for the first time in its history, opened up the political process of the Soviet Union for genuine elections. The effect was dramatic; in the non-Russian “republics of the SSR”, particularly Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia along the Baltic coast, non-Russian Deputies gained majorities and started declaring “independence”. In the Russian SFSR, Boris Yeltsin was back and was able to return to Moscow.

Boris Yeltsin got elected first as a Deputy to the Russian Supreme Soviet and then, in the next elections as the President of the Russian Federation. And while Russia was not declaring “independence” yet, by now both reformist and conservative Russian politicians supported an increase in the power of the local governments (that is, their own) at the expense of the power of the Central Soviet government.

On the same day that Yeltsin won the election to be the president of Russia: 12 June, 1990, Russia declared its “sovereignty” and thereby limited the application of the laws of the USSR on Russian territory, particularly the laws concerning finance and the economy.

Gorbachev however was vehemently opposed to this trend and at one point particularly directed his anger at the Baltic States. However, faced with the centrifugal forces of nationalism but not wanting to destroy all the reforms he had spent a lifetime to initiate by resorting to Stalinist style repression, Gorbachev tried to preserve the (Soviet) Union by binding it together with a new, more liberal Union Treaty.

Old style Communists, particularly in the State Security Apparatus, were shocked, outraged and terrified by what they were seeing happening to their “beloved motherland” and they didn’t see anything wrong with Stalinist style repression either. On 11 December 1990, the Chairman of the KGB, Vladimir Kryuchkov, made a “call for order” over the central television channel in Moscow. Then he started planning for a “state of emergency” at some future time. He invited the Defense Minister of the USSR, Dmitriy Yazov, the Interior Minister, Boris Pugo (formerly from the Latvian SSR), the Prime Minister, Valentin Pavlov, the Vice President, Gennady Yanayev, the deputy Chief of the Defence Council, Oleg Baklanov, the head of Gorbachev’s secretariat, Valery Boldin, and a Soviet Central Committee Secretary, Oleg Shenin to participate in the conspiracy. And he placed Gorbachev under KGB surveillance.

On 29 July 1991, Gorbachev, Yeltsin and the Kazakh President, Nursultan Nazarbayev held a meeting in Moscow, in which they discussed the possibility of replacing hardliners like Pavlov, Yazov, Kryuchkov and Pugo. Then, on 4 August, Gorbachev went on vacation to the Crimea.

The 29 July conversation had been eavesdropped on by the KGB. Furthermore, upon Gorbachev’s planned return to Moscow on 20 August, the Union Treaty which would redefine the balance of power in the USSR was to be signed. So the conspirators ordered 250,000 pairs of handcuffs from a factory in Pskov to be sent to Moscow, Kruchkov doubled the pay of all KGB personnel, cancelled all leaves and placed them on alert and Lefortovo prison was emptied to receive prisoners.

On 17 August the conspirators made the final decision to act. On 18 August a delegation consisting of Oleg Baklanov, Valeriy Boldin, Oleg Shenin, and Deputy Defense Minister, General Valentin Varennikov, flew to the Crimea and presented Gorbachev with an ultimatum: either declare a state of emergency, or resign and appoint Vice President Gennady Yanayev as acting president so as to allow the conspirators to “restore order” in the nation. Gorbachev refused to do either. He was then placed under house arrest by KGB personnel and cut off from all means of communication.

Upon the return of the delegation to Moscow, the conspirators announced the creation of the “State Committee of the State of Emergency”,to manage the country and to effectively maintain the regime of the state of emergency. The Committee members were: Gennady Yanayev, Valentin Pavlov, Vladimir Kryuchkov, Dmitriy Yazov, Boris Pugo, Oleg Baklanov, Vasily Starodubtsev and Alexander Tizyakov.

At 7 AM (Moscow time) on 19 August, 1991, the statement of the State Emergency Committee started getting broadcast over the Soviet central radio and TV channels. The three non-USSR transmitters (including the Russian Federation Radio Station and TV Station) were cut off the air. Four Deputies of the Russian Federation were immediately arrested, but Yeltsin was not one of the four. Military forces, including Red Army units with tanks and armored personnel carriers were sent to occupy key points in the city.

At 9 AM, Yeltsin having arrived at the Russian Supreme Soviet building (the Russian “White House”) issued a joint declaration with the Russian Federation Prime Minister Ivan Silaev and acting First Secretary of the Russian Supreme Soviet Ruslan Khasbulatov, stating that an illegal coup was taking place, urging the military not to support it and calling for a General Strike to demand that Mikhail Gorbachev address the people (which of course would have necessitated releasing him from arrest). Without access to the electronic media, this declaration was distributed the old way, by printed flyers.

Despite the building being ringed by a unit of tanks from the Tamanskaya Motor Rifle Division, that afternoon the people of Moscow began to gather around the White House and erect barricades. Then Major Evdokimov, commander of the tank unit, declared his loyalty to the leadership of the Russian Federation and allowed Yeltsin to climb on one of the tanks and address the crowd. Somehow, this episode got included in the evening news program broadcast by the State TV. From that time on, Boris Yeltsin was world famous.

At noon the next day: 20 August, General Kalinin, who had been appointed by Yanayev as the military commandant of Moscow, declared a curfew in Moscow, effective from 11 p.m. to 5 a.m. This was considered by many to be an indication that an attack on the White House was being planned.

That afternoon Kryuchkov, Yazov and Pugo made the decision to order an attack. Kryuchkov’s second in command, KGB general Ageev and Yazov’s second in command, Army general Achalov, planned “Operation Grom” (Thunder). The units to be involved were two KGB Special Forces detachments, “Alpha” and “Vympel”, and paratroopers. These were to be backed up by OMON Special Police, KGB Internal Security troops of the Dzerzhinsky division, three tank units and a helicopter squadron.

But Yeltsin had a defense committee led by General Konstantin Kobets, an elected Russian Federation Deputy and which including a number of other retired generals who had volunteered to defend the White House; some volunteers were armed. That evening Major Evdokimov’s tank unit was withdrawn. This was understood to be the sign that the attack was imminent.

To gather intelligence for the attack, the commander, General Viktor Karpukhin and other senior officers of Detachment “Alpha” together with General Alexander Lebed, deputy commander of the Airborne Troops, mingled with the crowds near the White House. After that, Viktor Karpukhin and the commander of Detachment “Vympel” Colonel Beskov tried to convince General Ageev that the operation was not a good idea, as it would inevitably result in bloodshed. Meanwhile, Alexander Lebed, with the consent of Pavel Grachev, the commander of the Airborne Troops, returned to the White House and secretly informed Yeltsin’s defense committee that the attack would begin at 2 AM, on the 21 August.

At about 1 AM, a column of BMPs (Infantry Fighting Vehicles) of the Tamanskaya Motor Rifle Division moving into position for the attack, was blocked in a tunnel by barricades made of trolleybuses and street cleaning machines. In the ensuing confrontation three unarmed demonstrators: Dmitriy Komar, Vladimir Usov and Ilya Krichevskiy were shot dead and several others wounded. The lead BMP was set on fire by the crowd, further blocking the tunnel, though no soldiers were killed.

When the intended time for the attack came, Detachments “Alpha” and “Vympel” did not move on the White House as planned. When Yazov learned about this, he, no doubt fearing widespread disobedience by the rank and file Russian soldiers if further attack orders were given, ordered the Army troops to pull out of Moscow; which they did starting around 8 AM on the 21st of August, 1991. Militarily the putsch was over.

The State Emergency Committee members met in the USSR Defense Ministry building to decide what to do next. The decision was made to send another delegation to talk to Mikhail Gorbachev. This delegation was made up of Vladimir Kryuchkov, Dmitriy Yazov, Oleg Baklanov, Alexander Tizyakov, Anatoliy Lukianov and Vladimir Ivashko. They arrived in the Crimea at 5 PM, but Gorbachev simply refused to meet them. Instead, he demanded that communications be restored and when they were: declared all decisions made by the State Emergency Committee void, dismissed all its members from government positions and ordered the USSR General Prosecutors Office to start a criminal investigation of the coup attempt.

Since a number of the leaders of regional executive committees had supported the State Committee of the State of Emergency, the Supreme Soviet of the Russian Federation by Decision Nr.1626-1, authorized President Yeltsin to appoint leaders of regional administrations, though the Russian constitution at the time did not give such authority to the President.

On 22 August, Gorbachev arrived back in Moscow. On the same day, Kryuchkov, Yazov and Tizyakov were arrested. Boris Pugo and his wife committed suicide when they came for him – or at least, that is the official version. On 23 Auguest Pavlov and Starodubtsev were arrested.

On the night of 23/24 August the statue of Feliks Dzerzhinskiy, the founder and first chief of the CHEKA, which stood in front of the KGB building at Dzerzhinskiy Square (Lubianka) was torn down.

On 24 August Baklanov, Boldin, and Shenin were arrested; Mikhail Gorbachev resigned from the office of General Secretary of the Soviet Communist Party; thousands of Muscovites took part in the funeral of Dmitriy Komar, Vladimir Usov and Ilya Krichevskiy; Mikhail Gorbachev posthumously awarded them the title of Hero of the Soviet Union; Boris Yeltsin asked their relatives to forgive him for not being able to prevent their deaths and issued Decree Nr. 83 which seized the archives of the Soviet Communist Party and transferred them to the State archive authorities.

On 25 August Boris Yeltsin issued Decree Nr. 90 nationalizing the property of the Soviet Communist Party on the territory of the Russian Federation (which included not only party committee headquarters but also educational institutions, hotels, etc.).

On 6 November, 1991, Boris Yeltsin issued Decree Nr.169 terminating the activity of the Soviet Communist Party in the Russian Federation.

Professor J. I. Grosvalds’ father, Janis Grosvalds had a prominent part in the abortive 1905 revolution and as a result had to flee Latvia, which he did through Klaipeda and Helsinki, emigrating to the United States of America. There Janis Grosvalds became a construction engineer and in time, with another man from Latvia, created a building materials factory which was located outside of Boston.

The crash of 1929 hit him quite hard and led him to return to Latvia. He had been an American citizen, but American law at the time required that a person in this situation return to the US at least every five years and when this proved inconvenient for him, he changed to Latvian citizenship. He also lived on Juras Str. and built a new house just down the street from the Emilija Benjamin House and at virtually the same time, though his was on a much smaller scale of course and finished two year earlier – in 1938.

The younger Grosvalds was born in 1927, in the USA and christened “John” with the very Latvian middle name of “Ilgars”. Because of the pronunciation issues involved, all his life he used Ilgars. He lived on Juras Str. until 1941 when he was 13 and again in 1942-44 and used to walk past the Benjamin house every day.

In the 1930s this was still the old wooden summer house that was quite near to the road and the fence was made of prefabricated panels. When the old house was torn down to make a place for the villa, the fence was sold, moved and reassembled, where it stood around another house for many more years. (It is completely gone now, however.)

In those days several “fierce” dogs roamed the property, but they could be fooled! When they started chasing the boy, barking, (along the inside of the fence) he would abruptly turn around and the dogs would reverse course all the way back to the corner of the property. But by the time they made the full run, he would have run past the other end of the Benjamin property.

One time as he was passing by, he overheard Emilija asking Juris to come and look at something; but Juris replied that it would have to wait, as he was behind the house with a shotgun, shooting crows. (Hunting crows was a common practice in the spring, in that era.)

The new Emilija Benjamin House was built from 1938 to 1940. It was faced with stucco made with white marble chips and shiny white mortar. As a result the house was a beautiful white and shimmered in the sun. (At this time it was common to stucco houses in Latvia with grey granite: but of course the result was a dark grey coloured house.)

A special hill (dune) was raised for the new house. Most material for the higher mound was sand taken from neighbouring dunes on the beach (there were no “dune protection laws” in those times) and 5 – 7 workers hauled sand in wheelbarrows for a year, to do this. After that the dune was covered in topsoil brought by a trainload from Germany but Ilgars did not see that part of it.

When the Soviet Occupation began (June 1940), one of their early edicts was the confiscation (“nationalization”) of all private houses of over 180 sq. meters (1901 sq. ft.) Since the Grosvalds’ house was 270 sq. meters they had to give it up, but they were “issued” a 4-room apartment fairly close nearby as a replacement, which had become vacant because it had belonged to a Baltic German.

Of course Emilija Benjamin’s house was also confiscated and was then used as the Residence for the commander of the Soviet Occupation Forces after Emilija was removed.

Because of his (1905) revolutionary credentials (and a very apparent, keen sense about when to compromise with the occupiers) the elder Mr. Grosvalds enjoyed a good relationship with the Communist Authorities and in the 1940-41 period was appointed the Chief Construction Engineer for Riga but nevertheless avoided being seen as a collaborator after the Germans liberated the city from the Communists in 1941.

During the German era the Grosvalds family regained title to their house on Juras Str., but during the nationalization period someone had fired up the special Swedish furnace improperly and the cast iron had cracked, so the house had no heat and could only be used summer.

By this time Emilija was dead and her heirs did not regain title of the Villa on Juras Str. (though they did get some other properties restored to them). Instead, after the Soviet General was chased away, the new German governor (Reichskommisar and Gauleiter, Lohse) moved in.

Reichskommissar Lohse had plans to create a large park around the Benjamin House and to raze the surrounding buildings, but the only things they got around to actually doing, were building an air-raid shelter (bunker) next to the house, which is now on the neighbouring hotel’s property and painting the formerly gleaming white house with camouflage stripes which, while faded, are still visible today. This was done in 1943, when the Soviet Air force was sufficiently reequipped, largely with American airplanes, to once again be a threat. Because of the location of the bunker the small street next to the house, leading to the beach, Vanaga Str. was closed and remains closed to this day. Also, in the 1930s Juras Str. was a dirt road. It was first asphalted during the German Occupation and the work was done by the R.A.D. (the Reichs Arbeits Dienst).

During the German era, security for the house was provided by a platoon of security personnel which Ilgvars Grosvalds believes were some sort of Police and not military troops. (He does not remember the uniforms well enough to describe the precise insignias.) The security detachment was billeted in the house at Juras Str. 6 (the Hasselbaum house) and the Benjamin House itself was routinely guarded by a three man shift. Reichskommissar Lohse used to move around in a closed (hard-top) car (I. Grosvalds did not recognize the make) which was always preceded by a military type car mounting a machine-gun.

Reichskommisar Alfred Rosenberg came to visit for one day and on that day was also scheduled to visit the City of Jelgava. There was very heavy security that day with a security officer stationed every 100 meters on the roads all through the City of Jurmala. Ilgars Grosvalds himself recalls seeing Reichskommissar Lohse one day (probably not the day of Rosenberg’s visit) as he came out through the big mechanically slide-able window in the front of the house in his Peacock Suit (this was the Latvian nickname for the, heavily “decorated”, brown, NSDAP Party, uniforms) and greet his arriving guests with the Nazi salute.

When the Soviets came back (late fall, 1944) the Grosvalds house was re-confiscated and because the entire zone around Juras Str. was now used as residences for high Soviet officials, no one from the family could even dare go near the area. There were actually two buildings on what had been the Grosvalds property and in 1959, the rear building burned down. Since it would not have done for the high Soviet officials to see a burned out building in their area, a battalion of Red Army soldiers was brought in and in two days all evidence of the building was removed and a dune of white beach sand created in its place.

Immediately after the war, Vilis Lacis, the man who was directly responsible for sending Emilija Benjamin to her death in Siberia, spent a lot of time at the Benjamin house, but was officially given a residence nearby, at the end of Undine Str. This house no longer exists. He lived there in 1945-46, but from 1946 onward had a residence in the “Marienbad Hotel” building.

The Benjamin house was used as an official guest house of the Soviet Government until the collapse of the Soviet Empire in 1991.

Janis Grosvalds passed away in 1960; in reply to a question as to why he had not tried to return to the USA, he explained that such an attempt “would not have been safe”. His father’s sister did however return to America in 1950 (it was safer for a woman to try to get permission for something like this), where the partner to the building materials factory bought out the Grosvalds share and with that money the sister bought a house in New York.

His son, (Professor) John Ilgars Grosvalds studied chemistry in the USSR in the 1950s and spent his life in that field.

After the restoration of the independence of the Republic of Latvia in 1991, Ilgars and his brother recovered title to their father’s property on Juras Str. but decided to sell it as they did not have the resources to restore what was left of the now dilapidated building. It took them over ten years to find a buyer and as the money had to be divided 8 ways there was not very much.

In the early 1990s Ilgars Grosvalds met Johanna Benjamin (the widow of Juris, the adopted son of Emilija) and was invited to the consecration of the Emilija Benjamin House after it had been restored to their family heirs. The Consecration was performed by the (Lutheran) Archbishop of Latvia, Rev. Gailitis and was accompanied by a musical performance by Inese Galanta at the piano and Maestro Kokars with the “Ave Sol” choir.

Johanna Benjamin lived in the house until her death in 1999.

〰

The History of the Emilija Benjamin House

The whole history of the 20th Century is wrapped up inside this house. Emilija Benjamin was quite conscious of the status that she had achieved as the most successful and wealthy person in Latvia and in many ways the final determinant of high style and culture in the country, and she chose her homes to reflect this fact. By the 1930s in addition to owning the fabulously successful publishing business, she had considerable real estate holdings, including several apartment and commercial buildings in Riga, among them, those housing her printing plant, a factory complex in Kekava (a town close to the south edge of Riga) and for personal use an impressive city residence located in the center of Riga that in those days was still sometimes known by the name of its original owners, as the Pfab Palace, as well as a country Estate called Waldeck and a summer house on land directly adjacent to the beach, in the resort city of Jurmala. The summer house had been one of her first houses and was a late 19th Century wooden building typical of the area. But, by the mid 1930s Emilija was ready to upgrade her summer residence.

The whole history of the 20th Century is wrapped up inside this house. Emilija Benjamin was quite conscious of the status that she had achieved as the most successful and wealthy person in Latvia and in many ways the final determinant of high style and culture in the country, and she chose her homes to reflect this fact. By the 1930s in addition to owning the fabulously successful publishing business, she had considerable real estate holdings, including several apartment and commercial buildings in Riga, among them, those housing her printing plant, a factory complex in Kekava (a town close to the south edge of Riga) and for personal use an impressive city residence located in the center of Riga that in those days was still sometimes known by the name of its original owners, as the Pfab Palace, as well as a country Estate called Waldeck and a summer house on land directly adjacent to the beach, in the resort city of Jurmala. The summer house had been one of her first houses and was a late 19th Century wooden building typical of the area. But, by the mid 1930s Emilija was ready to upgrade her summer residence.

Her first concrete step in the plan was to purchase the neighbouring lot directly adjacent (to the east) of her existing lot, effectively doubling the land available to her.As with everything she did, Emilija determined the new beach residence would be second to none, in fact the most exclusive house in Latvia. To draw up the plans she commissioned the famous German architect Lange and then personally worked with him on the design.

The transformation of the place started with a transformation of the landscape itself. Unlike all the other (wooden) houses on the street at that time, which nestled behind the dunes for protection from the winds, this building would sit on the crest of a bluff specially made for it. Local residents, who still remember the house being built, recall half a dozen workers hauling sand in wheelbarrows for two years to make the hill. Then it was covered with topsoil brought in from Germany. Special German topsoil had been bought as premium potting soil by the bag, in Latvia, for years. But Emilija Benjamin brought in a trainload. The standard customs duties (over 100 000 lats) on such a quantity turned out to be a shock even for Mrs. Benjamin and she ended up negotiating a settlement on the matter with the Latvian Government.

In 1938, construction was ready to begin and lasted over a year. The design and layout of the house was thoroughly modern, with, for that era, huge windows. Architect Lange was famous for his use of natural light and here he used his talents in the fullest. The windows were carefully sited to provide optimal views to the outside and to provide optimal illumination for the inside. Seaward was a three piece curved window running the full width of the dining room, but to the landward side was a glass wall running the full width of the central hall, which in the summer could be lowered into the floor by electric motors, opening the house wide to fresh breezes and the warmth of the sun, as this was also the south side of the building.

The motorized glass wall was not the only ultra-modern feature of the house. There were fixtures of aluminum, a metal as precious as gold at the time and of Bakelite, the just developed, forerunner of modern plastics.

At the same time, the design and overall look of the house, set far back from the road, was neo-classical and unmistakably declared that this owner had no need to show off.Along the roadside, the property was delineated by a wrought iron fence, designed separately by Architect A. Antonov and specially hand made in Paris and with the monogram “EB”, hammered into the design of the front gate. The monogram was also repeated in the wrought iron railing of the front balcony on the house.

On the other side of course, the house also featured a private, lockable, entrance to the beach. The turn of the century (19th to 20th) teahouse right on the top of the sea wall was also retained.

But however grand was Emilija’s dream, fate cut it cruelly short. Her husband Anton, died just before the Benjamin House, for that was what the place came to be known as, was finished and Emilija ended up moving in, alone. And she herself was only to live there for a couple of months. For, in 1939, the great dictators had decided a “future” for Eastern Europe and for the millions living there.

But however grand was Emilija’s dream, fate cut it cruelly short. Her husband Anton, died just before the Benjamin House, for that was what the place came to be known as, was finished and Emilija ended up moving in, alone. And she herself was only to live there for a couple of months. For, in 1939, the great dictators had decided a “future” for Eastern Europe and for the millions living there.

In 1940 Latvia was occupied, its Government overthrown and its society “socialized” by the Soviet Union. Emilija was summarily moved out of all her homes, initially “given” a small flat, but as a prime, in fact the prime, example of the “bourgeois”, soon enough arrested, shipped by cattle car to a labor camp and allowed to die.

The grandest home in her former country would now be the residence of the new determinant of order here, the commander of the Red Army occupation forces, Colonel-General Aleksandr Loktionov. He got to live in the house a few months longer than Emilija. Then the Germans came along and swiftly put the Red Army to flight; so swiftly that scapegoats had to be found and heads would have to roll. Just as he was leaving the area, General Loktionov was arrested by the NKVD and soon enough, shot without trial. He died less than 5 weeks after Emilija did.

With the advance of the Wehrmacht, the next new order had arrived. While the survivors of the Benjamin family received some of the properties the communists had confiscated (“nationalized”) back from the German Government, this grand house was not among them. After all, the next ruler of Latvia (and Lithuania, Estonia and Belorussia – the new National Socialist “Ostland”) needed a residence befitting him. So, Gauleiter Hinrich Lohse, the Reichskommissar of Ostland, moved in. He actually got to live in the house for several years. While there, his most famous visitor was Alfred Rosenberg, the Russian educated chief of ideology of the National Socialist German Workers (Nazi) Party, who apparently only stayed a few hours.

Gauleiter Lohse too had grand plans. Rumor had it, that he had intended to raze the smaller neighbouring buildings and create a large park, but he never got to that. However, during this period the street in front of the house, Juras Str. was paved for the first time, with the work being done by the R.A.D. (“Reichsarbeitsdienst” – the Empire’s Labor Service.)

As the war gradually turned against Germany, Hinrich Lohse became increasingly concerned about his personal safety. The consequences of that are still visible today. The house, which had originally been finished in beautiful white marble stucco that shimmered in the sun, was repainted with camouflage stripes to make it less visible to enemy aircraft. The greenish and brownish stripes, while faded, are still visible today.Just across the little side street, a bunker / air-raid shelter was built and the street was closed to all traffic. The bunker still exists and the street is still closed today.During Lohse’s time there, protection for the house and its occupant was provided by a platoon of security troops. The security detachment however was billeted down the street, in the house at Juras Str. 6 and the Benjamin House itself was routinely guarded by a three man shift. Gauleiter Lohse himself used to move around in a closed car which was always preceded by a military type vehicle mounting a machine-gun.

By autumn 1944, Lohse was gone. Just before leaving, he ordered removal vans and had the specially-made furniture, fine cutlery and other valuable items packed and taken to Germany. He took everything except for some essential items he would require for the remainder of his stay. After the war Alfred Rosenberg was tried and hung in Nuremberg; but, however the Allied Powers decided these things, Hinrich Lohse was not executed and passed away of natural causes in his native Muhlenbarbek, in Northern Germany in1964.

With the return of the Red Army, the house again became the residence of the “most equal of the equal” Soviet citizens; that is: the highest ranking Communist Party members. Immediately after the war, the now Chairman of the Latvian Communist Party, Vilis Lacis, one time employee and protegee of Emilija Benjamin and the man who actually signed the order sending her to her death, was reported to have enjoyed spending time there. The authorities in the Kremlin never actually allowed him to move in however, instead officially giving him a smaller house nearby (at the end of Undine Str.) where he lived in 1945-46. But from 1946 onward he had a residence in the “Marienbad Hotel” building at the far end of Juras Street.

Little is known about the specifics of whom and what was in the Benjamin house during the period immediately after the war, as the Soviet Regime pulled its customary thick curtain of secrecy around everything. Now, instead of the area being turned into a park as Lohse had dreamed, the entire neighbourhood was turned into a closed Soviet Government zone and gradually various other government buildings for mixed official and official leisure use, were put up nearby. The Benjamin house however remained as the jewel in the crown, to be used as an official guesthouse for the highest of guests.

Nikita Khrushchev, Mikail Gorbachev, Richard Nixon and Boris Yeltsin were among them. The longtime chairman of the French Communist Party Georges Marchais, stayed there repeatedly; “to relax” he said, presumably from the strain of being the most equal of proletarians in France.

Due to the importance of the persons present, the house received progressively more elaborate communications equipment during this era and the staff boasted that any Soviet Embassy anywhere in the world could be contacted directly from there any time of day or night. Vestiges of the switchboard setup are still present and visible today.

During the 1970s a major reconstruction project was undertaken in the basement level: an imitation log-cabin sauna was built in, complete with a small dipping pool. The well known Latvian artist, U. Zemzaris created a background painting for the sauna.

For a time, the new chairman of the Latvian Communist Party, August Voss, did manage to get the house as his personal residence and as he was an avid film fan, his contribution to the house was a complete movie theater, with a full size (twin 35mm film projectors) projection booth, installed in the basement. All the equipment is still there today as a silent witness to history, though of course for actual use, new computer driven digital projection equipment was recently installed directly in the viewing auditorium, by the current owner.

In 1986, architect Maris Gundars made minor additional changes to the interior, creating a new cloak room setup, new railings for the stairs as well as renewing the interior paint job. To maintain the unity of the appearance of the house he researched1930s styles for inspiration.

But it was during the endgame in the collapse of the Soviet Empire that the house again took its place in the forefront of history. As each of the three Baltic countries, Latvia, Estonia and Lithuania, started demanding the right to exercise the provision in the Constitution of the USSR that theoretically allowed constituent Republics to leave the “Union”, in essence, demanding the restoration of their independence; the house was used as the meeting place of the Baltic Council, which acted as a coordinating group between the three leaderships in their struggles with the Kremlin, in the campaign to provide information to the Western democracy’s concerning the struggle and as a place for the leaderships to negotiate among themselves without Moscow’s interference. The President of the Russian SSR at the time, BorisYeltsin also used the house as a sort of haven during the struggle in the Kremlin.

The most important event of all was the meeting between Mr. Gorbunovs (the leader of Latvia), Mr. Landsbergis (the leader of Lithuania), Mr. Rüütel (the Leader of Estonia) and Mr. Yeltsin, which took place in the “music room”, in which, in the summer of 1991, Mr. Yeltsin gave the Russian Federation’s support to the restoration of the independence and freedom of these three Countries which the Soviet Union had invaded and destroyed in 1940.

After these events, the former Soviet, now Russian Government turned the house over to the new Government of the Republic of Latvia. While from the beginning it was the avowed intention of the Latvian Government to restore property confiscated by the Communists to their rightful owners or heirs, that process took time. So, for several more years the house was used as an official government guesthouse by the Latvian Government, hosting many Prime Ministers, leaders of parliaments and delegations from as far as Australia and Israel.

During this period several very significant documents for the Baltic Countries were signed in Jurmala and the meeting with the Swedish Prime Minister Carl Bilt before the Helsinki Summit took place here. Karina Petersone, then assistent to Mr. Gorbunovs who at the time was the Chairman of the Higher Council of the Latvia (the official ruling body of the Latvian SSR which at this point was left over as a transitional authority until the first free national elections could be held in the country) relates how in June 1992, the members of the Baltic Council met with the Carl Bildt at the house. The CSCE Summit was to be held in Helsinki starting on 9 June, with both President Bush of the USA and President Yeltsin of Russia attending and the completion of the withdrawal of Russian troops from the Baltic nations was on the agenda. The US Government had asked Mr. Bildt to be a mediator between Russia and the Baltic nations on this issue and so Bildt, Rüütel, Landsbergis and Gorbunovs and one other person, Karina Petersone as the translator into three languages simultaneously, met to discuss it. A joint consensus by all four parties was reached and a resolution passed by acclaim with no vote necessary. The significance of that was explained by Anatolijs Gorbunovs who stated, “And maybe there, maybe in a way also in tandem with Yeltsin, the (Russian) troops were withdrawn, but the beginning was the Helsinki Summit, where … Mr. Yeltsin signed the documents. But in fact everything had already been decided in Jurmala, in this house.”

Finally, in November 1995 the house was restored to Emilija Benjamin heirs: her nephew Peter Aicher and her adopted son George Benjamin’s (né Aicher). In the beginning of 2000 the Aicher heirs bought the shares of the George Benjamin heirs and thus Peter Rudolf Aicher and his three sisters Anna Maria, Katharina and Alexandra are the joint owners of Juras street 13.